Fight fake news by educating

Kate Decker

Jul 1, 2020

What do Thomas Jefferson, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon and Donald Trump have in common other than leading the United States as president in our 244 years as a democracy?

They all waged wars with the press … and by extension, democracy.

Jefferson, Johnson, Nixon and now Trump, would follow the same pattern: deny that a solid news piece was truth, aim to discredit the news source and avoid accountability.

The only difference in the war Trump rages now than those who did before him is that now, anyone has the ability to reach the masses without the press.

And now, when we encounter stories on social media — quickly, as we’re scrolling, scrolling and managing several other tasks — it is hard to distinguish a credible source from a group or individual with an ulterior motive.

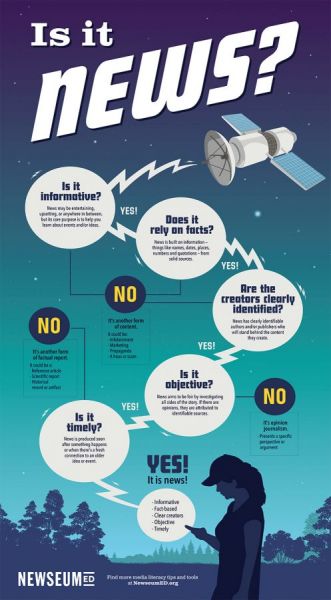

That is why it is more important than ever for newspapers to educate readers about media literacy. Media literacy is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create and act in a variety of forms.

Jessi Hollis McCarthy, outreach educator for the Freedom Forum — a nonpartisan 501 (c)(3) foundation that fosters First Amendment freedoms for all — hosted the webinar, “Fighting Fake News” on June 24 and clarified the phrase that our 45th president has made so popular.

Opinion content — as expressed on a newspaper’s Opinion pages — is not “fake news.”

Flawed news is not “fake news.” “Real people make mistakes,” McCarthy said. “The mark for journalism is … do they own up to it, issue a correction?”

Satire — like The Onion — is not “fake news.”

Even biased content — presenting a perspective or “take on the issue” — is not “fake news.”

“Fake news” is information that is not true but attempts to disguise itself as factual reporting, publishers even going as far as to print “fake” newspapers.

McCarthy cited an example from her residence of Washington, D.C., where someone printed a false Washington Post with a front-page stating Donald Trump had left the White House.

Using media literacy, they were able to determine it was not valid because a motto different than newspaper’s famous motto, Democracy Dies in Darkness, was listed under the fake masthead.

The contact information on the staff page also referred readers to staff emails that were not on the Washington Post’s website domain.

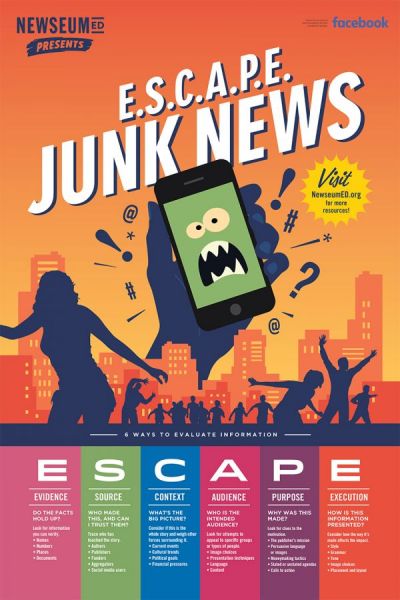

The acronym, ESCAPE, offers steps to follow to analyze a source or piece.

• Evidence – do the facts hold up? Look for facts to verify names, numbers, places and documents.

The motto being incorrect was an evidence red flag.

• Source – who made this and can I trust them? Trace who has touched the story: authors, publishers, funders, aggregators and social media users.

As previously mentioned, the staff page referred readers to publishers, editors and authors outside the Post’s network.

• Context – what’s the big picture? Consider if this is the whole story and weigh other forces surrounding it: current events, cultural trends, political goals and financial pressures.

If the president had actually stepped down, people would be talking about it, and there would be a lot of reports.

• Audience – who is the intended audience? Look for attempts to appeal to specific groups or types of people, for example, content geared towards Democrats or Republicans.

The pieces in the newspaper were lies, political in nature and clearly aimed at a Democratic audience.

• Purpose – why was this made? Look for clues to the motivation: publisher’s mission, persuasive language or images, money making tactics, stated or unstated agendas and calls to action.

• Execution – how is this information presented? Consider the way it’s made and how it affects the impact: style, grammar, tone, image choice, placement and layout.

Clearly, the publishers were trying to inspire confidence by presenting the information as a printed newspaper.

And that was a sound choice. …

In the National Newspaper Association's 2019 readership survey of more than 1,000 people from rural and urban communities across the United States, community newspapers topped all other mediums for trustworthiness regarding learning about candidates for public office.

With the coronavirus threat, newspapers have more eyeballs than usual; take advantage, and educate those normally nonreaders. Teach them that you do all this evaluating so it's easier for them to just read your newspaper than sift through all the stories online.

With the strong saturation of social media users, media literacy will stay a timely topic for the foreseeable future. Add media literacy to your ongoing stories list.

Get started with the Freedom Forum’s resources including teacher’s plans at https://newseumed.org/.

Kate Richardson is the managing editor of Publishers’ Auxiliary and the associate director of the NNA. Email her at kate@nna.org.